History

Forging is one of the oldest known metalworking processes. Traditionally, forging was performed by a smith using hammer and anvil,

though introducing water power to the production and working of iron in

the 12th century allowed the use of large trip hammers or power hammers

that exponentially increased the amount and size of iron that could be

produced and forged easily. The smithy or forge

has evolved over centuries to become a facility with engineered

processes, production equipment, tooling, raw materials and products to

meet the demands of modern industry.

In modern times, industrial forging is done either with presses

or with hammers powered by compressed air, electricity, hydraulics or

steam. These hammers may have reciprocating weights in the thousands of

pounds. Smaller power hammers,

500 lb (230 kg) or less reciprocating weight, and hydraulic presses are

common in art smithies as well. Some steam hammers remain in use, but

they became obsolete with the availability of the other, more

convenient, power sources.

Advantages and disadvantages

Forging can produce a piece that is stronger than an equivalent cast or machined part. As the metal is shaped during the forging process, its internal grain

deforms to follow the general shape of the part. As a result, the grain

is continuous throughout the part, giving rise to a piece with improved

strength characteristics. Additionally, forgings can target a lower total cost when compared to a

casting or fabrication. When you consider all the costs that are

involved in a product’s lifecycle from procurement to lead time to

rework, then factor in the costs of scrap, downtime and further quality

issues, the long-term benefits of forgings can outweigh the short-term

cost-savings that castings or fabrications might offer.

Some metals may be forged cold, but iron and steel are almost always hot forged. Hot forging prevents the work hardening

that would result from cold forging, which would increase the

difficulty of performing secondary machining operations on the piece.

Also, while work hardening may be desirable in some circumstances, other

methods of hardening the piece, such as heat treating, are generally more economical and more controllable. Alloys that are amenable to precipitation hardening, such as most aluminium alloys and titanium, can be hot forged, followed by hardening.

Production forging involves significant capital expenditure for

machinery, tooling, facilities and personnel. In the case of hot

forging, a high-temperature furnace (sometimes referred to as the forge)

is required to heat ingots or billets.

Owing to the massiveness of large forging hammers and presses and the

parts they can produce, as well as the dangers inherent in working with

hot metal, a special building is frequently required to house the

operation. In the case of drop forging operations, provisions must be

made to absorb the shock and vibration generated by the hammer. Most

forging operations use metal-forming dies, which must be precisely

machined and carefully heat-treated to correctly shape the workpiece, as

well as to withstand the tremendous forces involved.

Processes

A cross-section of a forged connecting rod that has been etched to show the grain flow

There are many different kinds of forging processes available, however they can be grouped into three main classes:

- Drawn out: length increases, cross-section decreases

- Upset: length decreases, cross-section increases

- Squeezed in closed compression dies: produces multidirectional flow

Common forging processes include: roll forging, swaging, cogging, open-die forging, impression-die forging, press forging, automatic hot forging and upsetting.

Temperature

All of the following forging processes can be performed at various

temperatures, however they are generally classified by whether the metal

temperature is above or below the recrystallization temperature. If the

temperature is above the material's recrystallization temperature it is

deemed hot forging; if the temperature is below the material's

recrystallization temperature but above 30% of the recrystallization

temperature (on an absolute scale) it is deemed warm forging; if below 30% of the recrystallization temperature (usually room temperature) then it is deemed cold forging. The main advantage of hot forging is that it can be done faster and more precise, and as the metal is deformed work hardening effects are negated by the recrystallization process. Cold forging typically results in work hardening of the piece.

Drop forging

Drop forging is a forging process where a hammer is raised and then

"dropped" onto the workpiece to deform it according to the shape of the

die. There are two types of drop forging: open-die drop forging and

closed-die drop forging. As the names imply, the difference is in the

shape of the die, with the former not fully enclosing the workpiece,

while the latter does.

Open-die drop forging

Open-die drop forging (with two dies) of an ingot to be further processed into a wheel

Open-die forging is also known as smith forging. In open-die forging, a hammer strikes and deforms the workpiece, which is placed on a stationary anvil.

Open-die forging gets its name from the fact that the dies (the

surfaces that are in contact with the workpiece) do not enclose the

workpiece, allowing it to flow except where contacted by the dies. The

operator therefore needs to orient and position the workpiece to get the

desired shape. The dies are usually flat in shape, but some have a

specially shaped surface for specialized operations. For example, a die

may have a round, concave, or convex surface or be a tool to form holes

or be a cut-off tool. Open-die forgings can be worked into shapes which include discs, hubs,

blocks, shafts (including step shafts or with flanges), sleeves,

cylinders, flats, hexes, rounds, plate, and some custom shapes. Open-die forging lends itself to short runs and is appropriate for art

smithing and custom work. In some cases, open-die forging may be

employed to rough-shape ingots

to prepare them for subsequent operations. Open-die forging may also

orient the grain to increase strength in the required direction.

Advantages of open-die forging

- Reduced chance of voids

- Better fatigue resistance

- Improved microstructure

- Continuous grain flow

- Finer grain size

- Greater strength

"Cogging" is the successive deformation of a

bar along its length using an open-die drop forge. It is commonly used

to work a piece of raw material to the proper thickness. Once the proper

thickness is achieved the proper width is achieved via "edging". "Edging"

is the process of concentrating material using a concave shaped

open-die. The process is called "edging" because it is usually carried

out on the ends of the workpiece. "Fullering"

is a similar process that thins out sections of the forging using a

convex shaped die. These processes prepare the workpieces for further

forging processes.

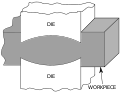

Impression-die forging

Impression-die

forging is also called "closed-die forging". In impression-die forging,

the metal is placed in a die resembling a mold, which is attached to an

anvil. Usually, the hammer die is shaped as well. The hammer is then

dropped on the workpiece, causing the metal to flow and fill the die

cavities. The hammer is generally in contact with the workpiece on the

scale of milliseconds. Depending on the size and complexity of the part,

the hammer may be dropped multiple times in quick succession. Excess

metal is squeezed out of the die cavities, forming what is referred to

as "flash".

The flash cools more rapidly than the rest of the material; this cool

metal is stronger than the metal in the die, so it helps prevent more

flash from forming. This also forces the metal to completely fill the

die cavity. After forging, the flash is removed. In commercial impression-die forging, the workpiece is usually moved

through a series of cavities in a die to get from an ingot to the final

form. The first impression is used to distribute the metal into the

rough shape in accordance to the needs of later cavities; this

impression is called an "edging", "fullering", or "bending" impression.

The following cavities are called "blocking" cavities, in which the

piece is working into a shape that more closely resembles the final

product. These stages usually impart the workpiece with generous bends

and large fillets.

The final shape is forged in a "final" or "finisher" impression cavity.

If there is only a short run of parts to be done, then it may be more

economical for the die to lack a final impression cavity and instead

machine the final features. Impression-die forging has been improved in recent years through

increased automation which includes induction heating, mechanical

feeding, positioning and manipulation, and the direct heat treatment of

parts after forging. One variation of impression-die forging is called "flashless forging",

or "true closed-die forging". In this type of forging, the die cavities

are completely closed, which keeps the workpiece from forming flash. The

major advantage to this process is that less metal is lost to flash.

Flash can account for 20 to 45% of the starting material. The

disadvantages of this process include additional cost due to a more

complex die design and the need for better lubrication and workpiece

placement. There are other variations of part formation that integrate

impression-die forging. One method incorporates casting a forging

preform from liquid metal. The casting is removed after it has

solidified, but while still hot. It is then finished in a single cavity

die. The flash is trimmed, then the part is quench hardened. Another

variation follows the same process as outlined above, except the preform

is produced by the spraying deposition of metal droplets into shaped

collectors (similar to the Osprey process). Closed-die forging has a high initial cost due to the creation of dies

and required design work to make working die cavities. However, it has

low recurring costs for each part, thus forgings become more economical

with more volume. This is one of the major reasons closed-die forgings

are often used in the automotive and tool industries. Another reason

forgings are common in these industrial sectors is that forgings

generally have about a 20 percent higher strength-to-weight ratio

compared to cast or machined parts of the same material.

Design of impression-die forgings and tooling

Forging dies are usually made of high-alloy or tool steel.

Dies must be impact resistant, wear resistant, maintain strength at

high temperatures, and have the ability to withstand cycles of rapid

heating and cooling. In order to produce a better, more economical die

the following standards are maintained:

- The dies part along a single, flat plane whenever possible. If not, the parting plane follows the contour of the part.

- The parting surface is a plane through the center of the forging and not near an upper or lower edge.

- Adequate draft is provided; usually at least 3° for aluminium and 5° to 7° for steel.

- Generous fillets and radii are used.

- Ribs are low and wide.

- The various sections are balanced to avoid extreme difference in metal flow.

- Full advantage is taken of fiber flow lines.

- Dimensional tolerances are not closer than necessary.

The dimensional tolerances of a steel part produced using the

impression-die forging method are outlined in the table below. The

dimensions across the parting plane are affected by the closure of the

dies, and are therefore dependent on die wear and the thickness of the

final flash. Dimensions that are completely contained within a single

die segment or half can be maintained at a significantly greater level

of accuracy.

| Mass [kg (lb)] | Minus tolerance [mm (in)] | Plus tolerance [mm (in)] |

|---|---|---|

| 0.45 (1) | 0.15 (0.006) | 0.46 (0.018) |

| 0.91 (2) | 0.20 (0.008) | 0.61 (0.024) |

| 2.27 (5) | 0.25 (0.010) | 0.76 (0.030) |

| 4.54 (10) | 0.28 (0.011) | 0.84 (0.033) |

| 9.07 (20) | 0.33 (0.013) | 0.99 (0.039) |

| 22.68 (50) | 0.48 (0.019) | 1.45 (0.057) |

| 45.36 (100) | 0.74 (0.029) | 2.21 (0.087) |

A lubricant is used when forging to reduce friction and wear. It is

also used as a thermal barrier to restrict heat transfer from the

workpiece to the die. Finally, the lubricant acts as a parting compound

to prevent the part from sticking in the dies.

Press forging

Press

forging works by slowly applying a continuous pressure or force, which

differs from the near-instantaneous impact of drop-hammer forging. The

amount of time the dies are in contact with the workpiece is measured in

seconds (as compared to the milliseconds of drop-hammer forges). The

press forging operation can be done either cold or hot.

The main advantage of press forging, as compared to drop-hammer

forging, is its ability to deform the complete workpiece. Drop-hammer

forging usually only deforms the surfaces of the work piece in contact

with the hammer and anvil; the interior of the workpiece will stay

relatively undeformed. Another advantage to the process includes the

knowledge of the new part's strain rate. We specifically know what kind

of strain can be put on the part, because the compression rate of the

press forging operation is controlled.

There are a few disadvantages to this process, most stemming from the

workpiece being in contact with the dies for such an extended period of

time. The operation is a time-consuming process due to the amount and

length of steps. The workpiece will cool faster because the dies are in

contact with workpiece; the dies facilitate drastically more heat

transfer than the surrounding atmosphere. As the workpiece cools it

becomes stronger and less ductile, which may induce cracking if

deformation continues. Therefore, heated dies are usually used to reduce

heat loss, promote surface flow, and enable the production of finer

details and closer tolerances. The workpiece may also need to be

reheated.

When done in high productivity, press forging is more economical than

hammer forging. The operation also creates closer tolerances. In hammer

forging a lot of the work is absorbed by the machinery, when in press

forging, the greater percentage of work is used in the work piece.

Another advantage is that the operation can be used to create any size

part because there is no limit to the size of the press forging machine.

New press forging techniques have been able to create a higher degree

of mechanical and orientation integrity. By the constraint of oxidation

to the outer layers of the part, reduced levels of microcracking occur

in the finished part.

Press forging can be used to perform all types of forging, including

open-die and impression-die forging. Impression-die press forging

usually requires less draft than drop forging and has better dimensional

accuracy. Also, press forgings can often be done in one closing of the

dies, allowing for easy automation.

Upset forging

Upset forging increases the diameter of the workpiece by compressing its length. Based on number of pieces produced, this is the most widely used forging process. A few examples of common parts produced using the upset forging process

are engine valves, couplings, bolts, screws, and other fasteners.

Upset forging is usually done in special high-speed machines called crank presses.

The machines are usually set up to work in the horizontal plane, to

facilitate the quick exchange of workpieces from one station to the

next, but upsetting can also be done in a vertical crank press or a

hydraulic press. The initial workpiece is usually wire or rod, but some

machines can accept bars up to 25 cm (9.8 in) in diameter and a capacity

of over 1000 tons. The standard upsetting machine employs split dies

that contain multiple cavities. The dies open enough to allow the

workpiece to move from one cavity to the next; the dies then close and

the heading tool, or ram, then moves longitudinally against the bar,

upsetting it into the cavity. If all of the cavities are utilized on

every cycle, then a finished part will be produced with every cycle,

which makes this process advantageous for mass production.

These rules must be followed when designing parts to be upset forged:

- The length of unsupported metal that can be upset in one blow without injurious buckling should be limited to three times the diameter of the bar.

- Lengths of stock greater than three times the diameter may be upset successfully, provided that the diameter of the upset is not more than 1.5 times the diameter of the stock.

- In an upset requiring stock length greater than three times the diameter of the stock, and where the diameter of the cavity is not more than 1.5 times the diameter of the stock, the length of unsupported metal beyond the face of the die must not exceed the diameter of the bar.

Automatic hot forging

The

automatic hot forging process involves feeding mill-length steel bars

(typically 7 m (23 ft) long) into one end of the machine at room

temperature and hot forged products emerge from the other end. This all

occurs rapidly; small parts can be made at a rate of 180 parts per

minute (ppm) and larger can be made at a rate of 90 ppm. The parts can

be solid or hollow, round or symmetrical, up to 6 kg (13 lb), and up to

18 cm (7.1 in) in diameter. The main advantages to this process are its

high output rate and ability to accept low-cost materials. Little labor

is required to operate the machinery.

There is no flash produced so material savings are between 20 and 30%

over conventional forging. The final product is a consistent 1,050 °C

(1,920 °F) so air cooling will result in a part that is still easily

machinable (the advantage being the lack of annealing required after

forging). Tolerances are usually ±0.3 mm (0.012 in), surfaces are clean,

and draft angles are 0.5 to 1°. Tool life is nearly double that of

conventional forging because contact times are on the order of

0.06-second. The downside is that this process is only feasible on

smaller symmetric parts and cost; the initial investment can be over $10

million, so large quantities are required to justify this process.

The process starts by heating the bar to 1,200 to 1,300 °C (2,190 to

2,370 °F) in less than 60 seconds using high-power induction coils. It

is then descaled with rollers, sheared into blanks, and transferred

through several successive forming stages, during which it is upset,

preformed, final forged, and pierced (if necessary). This process can

also be coupled with high-speed cold-forming operations. Generally, the

cold forming operation will do the finishing stage so that the

advantages of cold-working can be obtained, while maintaining the high

speed of automatic hot forging.

Examples of parts made by this process are: wheel hub unit bearings,

transmission gears, tapered roller bearing races, stainless steel

coupling flanges, and neck rings for LP gas cylinders. Manual transmission gears are an example of automatic hot forging used in conjunction with cold working.

Roll forging

Roll

forging is a process where round or flat bar stock is reduced in

thickness and increased in length. Roll forging is performed using two

cylindrical or semi-cylindrical rolls, each containing one or more

shaped grooves. A heated bar is inserted into the rolls and when it hits

a spot the rolls rotate and the bar is progressively shaped as it is

rolled through the machine. The piece is then transferred to the next

set of grooves or turned around and reinserted into the same grooves.

This continues until the desired shape and size is achieved. The

advantage of this process is there is no flash and it imparts a

favorable grain structure into the workpiece.

Examples of products produced using this method include axles, tapered levers and leaf springs.

Net-shape and near-net-shape forging

This process is also known as precision forging. It was

developed to minimize cost and waste associated with post-forging

operations. Therefore, the final product from a precision forging needs

little or no final machining. Cost savings are gained from the use of

less material, and thus less scrap, the overall decrease in energy used,

and the reduction or elimination of machining. Precision forging also

requires less of a draft, 1° to 0°. The downside of this process is its

cost, therefore it is only implemented if significant cost reduction can

be achieved.

Cold Forging

Near

net shape forging is most common when parts are forged without heating

the slug, bar or billet. Aluminum is a common material that can be cold

forged depending on final shape. Lubrication of the parts being formed

is critical to increase the life of the mating dies.

Cost implications

To achieve a low-cost net shape forging for demanding applications that are subject to a high degree of scrutiny, i.e. non-destructive testing

by way of a dye-penetrant inspection technique, it is crucial that

basic forging process disciplines be implemented. If the basic

disciplines are not met, subsequent material removal operations will

likely be necessary to remove material defects found at non-destructive

testing inspection. Hence low-cost parts will not be achievable.

Example disciplines are: die-lubricant management (Use of

uncontaminated and homogeneous mixtures, amount and placement of

lubricant). Tight control of die temperatures and surface finish /

friction.

Induction forging

Unlike the above processes, induction forging is based on the type of

heating style used. Many of the above processes can be used in

conjunction with this heating method.

Multidirectional forging

Multidirectional

Forging is forming of a work piece in a single step in several

directions. The multidirectional forming takes place through

constructive measures of the tool. The vertical movement of the press

ram is redirected using wedges which distributes and redirects the force

of the forging press in horizontal directions.

Materials and applications

Forging of steel

Depending on the forming temperature steel forging can be divided into:

- Hot forging of steel

- Forging temperatures above the recrystallization temperature between 950 - 1250 °C

- Good formability

- Low forming forces

- Constant tensile strength of the workpieces

- Warm forging of steel

- Forging temperatures between 750 – 950 °C

- Less or no scaling at the workpiece surface

- Narrower tolerances achievable than in hot forging

- Limited formability and higher forming forces than for hot forging

- Lower forming forces than in cold forming

- Cold forging of steel

- Forging temperatures at room conditions, self-heating up to 150 °C due to the forming energy

- Narrowest tolerances achievable

- No scaling at workpiece surface

- Increase of strength and decrease of ductility due to strain hardening

- Low formability and high forming forces are necessary

For industrial processes steel alloys are primarily forged in hot

condition. Brass, bronze, copper, precious metals and their alloys are

manufactured by cold forging processes, while each metal requires a

different forging temperature.

Forging of aluminium

- Aluminium forging is performed at a temperature range between 350 and 550 °C

- Forging temperatures above 550 °C are too close to the solidus temperature of the alloys and lead in conjunction with varying effective strains to unfavorable workpiece surfaces and potentially to a partial melting as well as fold formation.

- Forging temperatures below 350 °C reduce formability by increasing the yield stress, which can lead to unfilled dies, cracking at the workpiece surface and increased die forces

Due to the narrow temperature range and high thermal conductivity,

aluminium forging can only be realized in a particular process window.

To provide good forming conditions a homogeneous temperature

distribution in the entire workpiece is necessary. Therefore, the

control of the tool temperature has a major influence to the process.

For example, by optimizing the preform geometries the local effective

strains can be influenced to reduce local overheating for a more

homogeneous temperature distribution.

Application of aluminium forged parts

High-strength

aluminium alloys have the tensile strength of medium strong steel

alloys while providing significant weight advantages. Therefore,

aluminium forged parts are mainly used in aerospace, automotive industry

and many other fields of engineering especially in those fields, where

highest safety standards against failure by abuse, by shock or vibratory

stresses are needed. Such parts are for example chassis parts, steering

components and brake parts. Commonly used alloys are AlSi1MgMn (EN AW-6082) and AlZnMgCu1,5 (EN AW-7075).

About 80% of all aluminium forged parts are made of AlSi1MgMn. The

high-strength alloy AlZnMgCu1,5 is mainly used for aerospace

applications.

Equipment

Hydraulic drop-hammer

(a) Material flow of a conventionally forged disc; (b) Material flow of an impactor forged disc

The most common type of forging equipment is the hammer and anvil.

Principles behind the hammer and anvil are still used today in drop-hammer

equipment. The principle behind the machine is simple: raise the hammer

and drop it or propel it into the workpiece, which rests on the anvil.

The main variations between drop-hammers are in the way the hammer is

powered; the most common being air and steam hammers. Drop-hammers

usually operate in a vertical position. The main reason for this is

excess energy (energy that isn't used to deform the workpiece) that

isn't released as heat or sound needs to be transmitted to the

foundation. Moreover, a large machine base is needed to absorb the

impacts.

To overcome some shortcomings of the drop-hammer, the counterblow machine or impactor

is used. In a counterblow machine both the hammer and anvil move and

the workpiece is held between them. Here excess energy becomes recoil.

This allows the machine to work horizontally and have a smaller base.

Other advantages include less noise, heat and vibration. It also

produces a distinctly different flow pattern. Both of these machines can

be used for open-die or closed-die forging.

Forging presses

A forging press,

often just called a press, is used for press forging. There are two

main types: mechanical and hydraulic presses. Mechanical presses

function by using cams, cranks and/or toggles to produce a preset (a

predetermined force at a certain location in the stroke) and

reproducible stroke. Due to the nature of this type of system, different

forces are available at different stroke positions. Mechanical presses

are faster than their hydraulic counterparts (up to 50 strokes per

minute). Their capacities range from 3 to 160 MN (300 to 18,000 short

tons-force). Hydraulic presses use fluid pressure and a piston to

generate force. The advantages of a hydraulic press over a mechanical

press are its flexibility and greater capacity. The disadvantages

include a slower, larger, and costlier machine to operate.

The roll forging, upsetting, and automatic hot forging processes all use specialized machinery.

No comments:

Post a Comment